Hotels with History

Classic grande dames are still offering a warm welcome in a changing world

September 30, 2019

When Business Traveler magazine held its annual Best in Business Travel awards ceremony at The Plaza Hotel in the aughts (with Queen Noor of Jordan as its MC) it was a very different world.

The hotel still had the patina of eighties excess from the days when Donald Trump owned what he called “a masterpiece, the Mona Lisa.” All the rooms were true hotel rooms (including the famous ones facing the park), the Oak Room was still very much abuzz (the star of scenes from Hitchcock’s North by Northwest to Streep and Hanks in The Post) and the constant stream of out-of-towners that whirled through its revolving doors never thought change would come to this New York landmark.

But change did come to the city and to the hospitality industry. Boutique hotels were on trend. Airbnb was born. A massive, old school heritage hotel with all its real estate eaten up by hotel room space was no longer sustainable.

In 2004, The Plaza was sold for $675 million to Israeli-owned El Ad Properties which closed the landmark, auctioned off its old furniture and converted 152 of its rooms into condominiums. All the Central Park-facing spaces went to the highest bidders. The Oak Room was closed and hotel aficionados held their breath to see if The Plaza could survive.

Today the hotel is now owned by Qatar-based Katara Hospitality, still a work of art but more of a modern masterpiece – a Damien Hirst rather than a Mona Lisa – and managed by Fairmont, king of the heritage hotel castle.

The Plaza now has 282 rooms and suites, some with partial park views and others decked out as new extraordinary themed suites. For example, the Eloise Suite designed by Betsey Johnson, is based on the famed children’s book heroine who in the stories lived at the Plaza. Another is the Fitzgerald Suite, created by Great Gatsby costume designer Catherine Martin (the Leo di Caprio version).

The Palm Court’s ceiling has been restored and unveiled and the clinking of champagne glasses is once again heard in the lobby. The Edwardian room, a massive wood-paneled ballroom sized space, is available for private events. And there is word that gem of a bar, the Oak Room, may open in some form at some time in the future.

The Plaza also benefited from The Waldorf Astoria’s temporary closing in 2017, obliging its Guerlain Spa (the only one on the East Coast) to move into the Plaza. Along with inspiring classic architecture, hotel guests can pamper themselves with Guerlain amenities in the bathroom and purchase heritage scents at the perfume bar.

The Waldorf Astoria, long the standard bearer for heritage hotels, has been in the news since its “temporary” closing in 2017. The hotel has now passed into the hands of the Chinese government and all signs point to a future, if vastly downsized opening. The Waldorf’s interior and exterior art deco embellishments have been landmarked by the city, but its future as a true hotel is uncertain. The current plan is to reduce the hotel rooms from 1,413 to 350 with the bulk of the remaining space being used as condominiums.

Sparkling Gems

Other legacy hotels have been luckier.

Fairmont’s two other American gems: The Copley Plaza and The Fairmont San Francisco are still very much alive and doing business as grande dame heritage hotels.

The Copley Plaza (named after Boston painter John Singleton Copley) was opened in 1912. The first American hotel to accept credit cards and the first hotel with an international reservations system, it quickly became the place to stay in Boston.

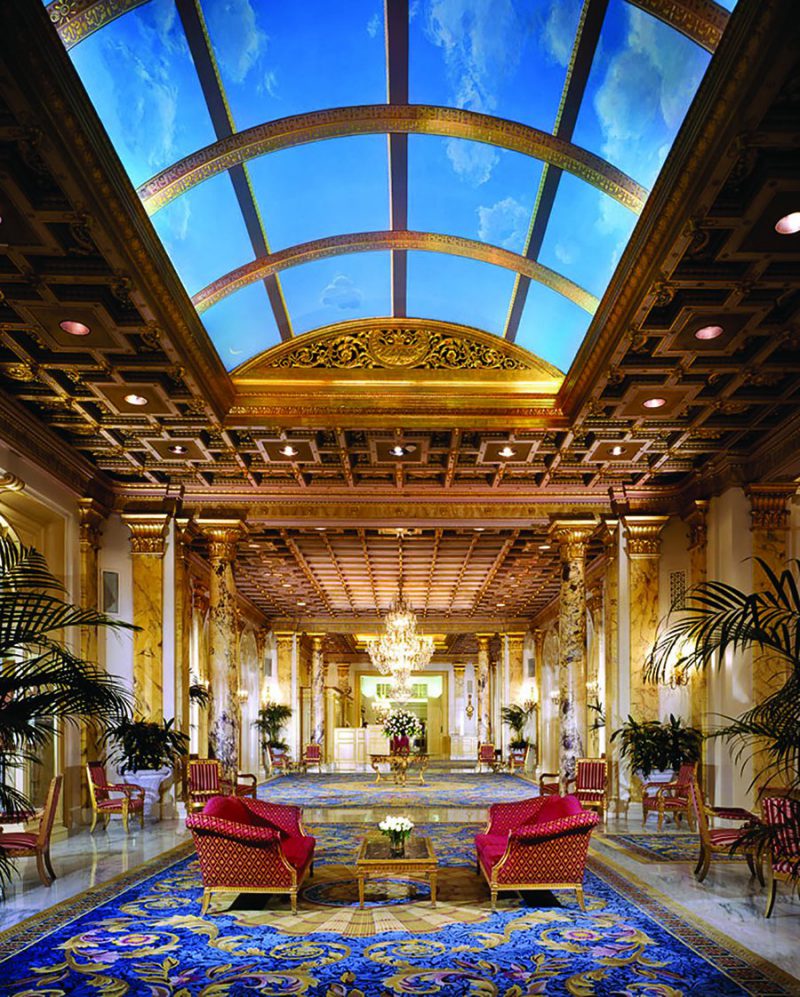

The hotel, like its sister Fairmont property The Plaza, was designed by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh. The 383-room hotel underwent a $30 million renovation between 2011 and 2012 but still maintains landmarks like its iconic entrance hall, Peacock Alley.

The Fairmont San Francisco remains enshrined in film lovers’ imaginations as the location of various scenes in the classic Hitchcock film Vertigo. Inside, the gilt and velvet are marvelously intact and although rooms have been divided to create more saleable space, the overall feel is pampered and plush. Businesses that rent corporate space can get access to the hotel’s exquisite Moorish designed rooftop enclaves with 360-degree views of the San Francisco skyline.

Washington, DC, has more than its share of well-preserved grande dames steeped in the nation’s heritage. Two are but a stone’s throw from the White House and have intimate connections with the capitol city’s halls of power.

The Hay-Adams Hotel on the corner of 16th and H Streets was once the site of two homes, one belonging to John Hay, who was a personal secretary to Abraham Lincoln and later Secretary of State under both William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. His neighbor, Henry Adams was a historian and Harvard professor, and a descendant of Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams. Guests of Hay and Adams through the years included such luminaries as Mark Twain, Henry James and Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1927 the homes were torn down and replaced by the current Italian Renaissance-style edifice, which still preserves many of the original historic artifacts including wood paneling from the John Hay house.

Around the corner at Pennsylvania Avenue and 15th Street, the 200-plus-year-old Willard – now the Willard InterContinental – has seen many of Washington’s history-makers come and go. This imposing classic originally started life as a string of humble row houses in 1816. Abraham Lincoln stayed here prior to his 1860 inauguration, and Julia Ward Howe penned the words to the Battle Hymn of the Republic in these walls. It’s said Ulysses Grant coined the term “lobbyist” because of his annoyance with the favor-seekers who prowled the Willard’s lobby.

The magnificent Beaux Arts façade was erected in 1901, but by 1969 the future of the hotel was hanging in the balance. Several ideas were floated for the property, but in the end it was decided that the best use was still as a hotel. It took over 18 years, but the restored Willard opened once again in 1986.

Modern Classics

Not as old, but no less a point of interest, the Watergate Hotel was recently renovated with a sly nod to its checkered history. The hotel gave its name to the scandal that ensued after the 1972 break-in here; the entire affair led to many high-profile prison terms and ultimately the resignation of Richard Nixon.

The space which had been broken into has been rebranded as “The Scandal Suite” and designed by Scandal TV show costume designer, Lyn Paolo. The room is filled with newspaper clippings from the time and, of course, with a cassette tape recorder and other accoutrements of 1970s break-in espionage.

In New York, another ‘70s icon, The Millennium Hilton New York One UN Plaza was reflagged in 2017 after a $68 million dollar facelift when it joined the Hilton brand. The hotel was built in 1976 and is the only building from that era to have been accorded landmark status. Its mirrored very-Studio 54-era lobby designed by Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo, was prestigiously named a New York City Landmark in 2017.

The Landmarks Commission said at the time, “Built in an era when relatively few new hotels were constructed in New York City, these nearly intact lavish interiors are a distinctive example of public spaces in the 1970s and 1980s.”

Along with the disco inferno-esque lobby, the hotel’s Ambassador Grill was also a major 1970s power watering hole where guests could sit cheek-by-jowl with Henry Kissinger, or perhaps Truman Capote who lived across the street. Today, the restaurant is helmed by Ayman Mustafa, a Millennial chef with Jordanian roots whose clean cuisine and Mediterranean flavor palate is bringing a new clientele to dine at the Grill.

Faraway Places

Outside the US, iconic heritage hotels like Morocco’s La Mamounia and Paris’ Ritz Hotel have recently redesigned and reinvented themselves for new generations of travelers. However one of the most instantly recognized hotels of all time, Singapore’s Raffles Hotel, seems to have taken to heart the mantra, “Everything old is new again.”

The hotel was opened in 1887 by the Sarkies brothers. These enterprising Armenians were savvy enough to name their property after Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, who established the British colonial presence in Singapore in 1819. Even though Raffles himself was long dead before the hotel opened, naming the property after him was a canny move by the Sarkies, virtually guaranteeing the hotel would forever be a Singapore institution.

As the hotel grew, so did its legendary status: The last tiger in Singapore was shot under Raffles’ bar (it had escaped from a circus); the eponymous Singapore Sling was invented at Raffles in 1915 (to allow proper ladies to imbibe in public); and there’s a photo gallery of guests from the worlds of royalty (Queen Elizabeth II), entertainment (Michael Jackson, Charlie Chaplin, Elizabeth Taylor) and literature (Noel Coward, James Michener, Somerset Maugham).

Maugham summed up the hotel’s near-mythic status: “Raffles stands for all the fables of the exotic East,” he wrote. But fabled as it was, Raffles was not immune to the ravages of time, nor the realities of modern travel. As it approached its centenary, Raffles – like so many of its grande dame sisters – was a bit down at the heels but still a commanding presence in the community.

As a consequence in 1987, the property was designated a National Monument by the Singapore government. Thus saved from the wrecking ball, the hotel found new investors and underwent extensive renovations, first in 1989 and more recently in 2017. Impeccably restored, the legendary hotel reopened in August, every bit as opulent (personal butlers, Singapore Slings) but with modern twists (wireless touchpad room controls, WiFi throughout).

While modern hotel concepts have flooded the market in recent years, there is still something warm and hospitable about these holdovers from a bygone era. Two things that all these magnificent old hotels have in common: It takes plenty of money to return them to their former glory, and more to keep them there. And it takes a will on the part of communities and investors to see the projects through.

Are these grande dames worth it? Only time will tell – and so far, it seems time is on their side.