Lifting The Clouds

A new president, a peace accord and a tourism boom signal a bright future for Colombia. But Bogotanos aren’t ready to party just yet

June 29, 2019

The Andean sun, veiled by passing clouds but deceptively strong, shines down on Plaza Bolivar. As ever, the square is thronging with tourists, SIM-card vendors, presidential guards in ceremonial uniform and children chasing pigeons. On one side, the magnificent neoclassical cathedral. Opposite is the town hall. A third building houses the Capitolio Nacional, seat of the national congress. The fourth is occupied by the Palace of Justice.

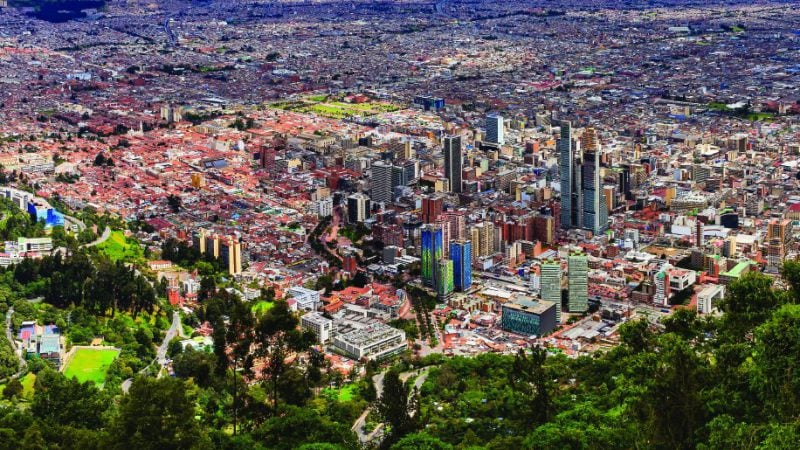

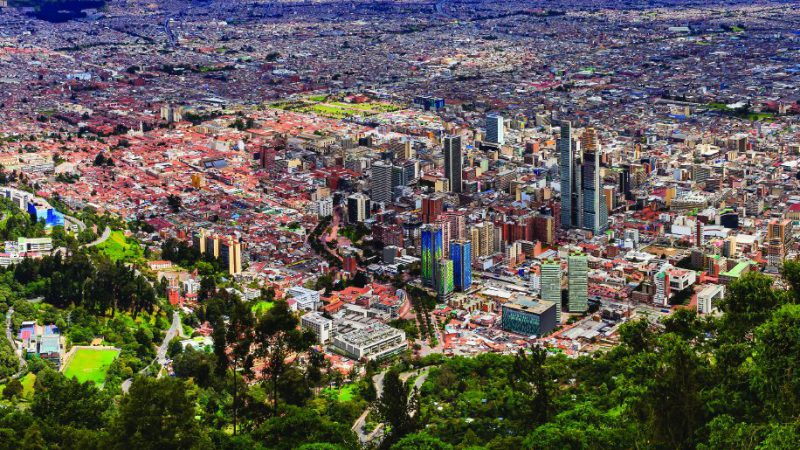

Whether here in La Candelaria – the cobblestoned historic center – or in Bogota’s skyscraper-strewn sprawl, Colombia’s past casts long shadows. Historians usually trace the nation’s well-reported woes to 1948 and the start of a ten-year civil war known as La Violencia. But the armed conflict that generated the image of a nation in thrall to drug lords, left-wing rebels and right-wing paramilitary groups probably peaked in the 1990s, when two-thirds of the world’s kidnappings occurred here, and the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) controlled up to a third of Colombia’s territory.

Beginning in 2002, the government of Alvaro Uribe gave the army greater powers to combat the guerrillas. His successor, Juan Manuel Santos, kept up the pressure and invited FARC to peace negotiations. The twin-pronged approach worked. Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace prize in 2016. On Sept. 1, 2017, FARC became a political party, parading through Plaza Bolivar.

In tandem with these changes, economic prospects have improved dramatically. Since 2011, direct foreign investment into Colombia has more than doubled and, according to the Ministry of Commerce, more than 1,100 foreign firms have set up operations in the country. In May, Colombia was invited to join Mexico and Chile as the third Latin American member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the select club of 36 wealthy, stable democracies.

But South America’s third largest economy, behind Brazil and Argentina, relies heavily on global commodity prices. Inevitably, Colombia reels whenever there is a downturn in the value of petroleum, coal, bananas, cut flowers or coffee. Economic growth slowed to 1.8 percent in 2017 – down from 2 percent the previous year (and way down from the 5-6 percent notched up before the crude oil crash of 2014).

However, the World Bank noted an upturn in financial services. And as the effects of the El Nino phenomenon dissipated last year, the agriculture sector expanded. “The agricultural sector has immense potential now that rural areas have seen the end of the war,” says Mauricio Rodriguez, formerly Colombia’s ambassador to the UK, and currently an advisor to Bogota’s mayor, Enrique Penalosa. “Even though peace is not fully consolidated, we are starting to enjoy the dividends, such as a boom in tourism and record high investment levels.”

Money Woes

Most observers concur that Colombia needs to turn its fragile peace into a comprehensive social contract that tackles crime, widespread corruption and social inequality. Reforms across business and banking are also needed.“The Colombian economy faces a number of structural challenges,” says Luis Carlos Reyes, assistant professor of economics at Bogota’s Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and co-founder of the Observatorio Fiscal, an ethics-focused think tank. “Oligopolies in several industries tend to run the show. This is the issue in the financial sector. It is difficult for entrepreneurs to find capital to fund new businesses, unless they get it from the established banks at rates that are not competitive.”

Reyes also points to difficulties entering the local stock market. Leading glassmaker Tecnoglass claimed that it was easier to join Nasdaq than the Colombian Stock Exchange. He also points to burdensome regulations on issuing bonds, fluctuations in the exchange rate – which makes borrowing abroad riskier – and an unpredictable tax regime.

“In summation,” Reyes says, “financial investing is harder than it should be unless you are a big player, and that is not good for the economy. We need more competitive financial markets.”

In May, Colombia elected a new president. Ivan Duque, 42, a member of the right-wing Democratic Center party and former ally of Uribe, was widely viewed as the business-friendly choice. “The new president was the candidate of the status quo,” says Reyes. “It was a choice between a candidate who was suspected of being anti-business and anti-market, and one who is at best pro-business but not really pro-market. In this sense, Duque may be better for the economy.”

From Gold to Gigabytes

The original pre-Colombian inhabitants of Bogota, the Muisca, were master goldsmiths, and the city’s Gold Museum is a world-class showcase of precious metalwork. Gold mining and other extraction industries have played a major part in the nation’s economic history. While the Colombian capital is often dubbed “the Athens of South America” (a nickname given by Prussian explorer Alexander Von Humboldt in the 19th century) for its cultural riches, Bogotanos tend to be business-minded and entrepreneurial in spirit.

With a population of more than eight million, Bogota is recognized as one of Latin America’s key business centers. A new terminal at El Dorado International airport opened in 2012. Recent hotel openings include a 297-room Grand Hyatt, a sleek W, two Four Seasons properties and the uber-cool BOG boutique hotel.

Bogota has a modern central business sector in the Chapinero district, well away from traffic-clogged La Candelaria. In January, the glass-walled 4,000-delegate capacity Agora convention center opened. In a bid to keep ahead of upstart smaller rival cities, Bogota styles itself as the tech and coworking capital: HubBOG, a “start-up campus” set up a decade ago, claims to have mentored more than 200 countries.

Two miles north of Chapinero are several districts known for dining and nightlife, including the Zona T, aka Zona Rosa, Zona G (for “gourmet”) and Parque de la 93. While still trailing Peru as a gastronomic center, Bogota chefs Harry Sasson and Leonor Espinosa are making waves, while out-of-town eatery Andres Carne de Res (and its in-town branch Andres DC) combines fun, dancing and great food in an effervescent Colombian style; branches of Lima’s Astrid y Gaston and Rafael are also found in the city.

Becoming a Business Hub

Behind the vivacious veneer, the city has some way to go to establish itself as a premier business hub. “It faces transit and public transport challenges, and security problems as well. Nevertheless, Bogota has positioned itself as a major Latin American capital for its strategic geographical position and diverse population,” says Juan Guillermo Moncada, a researcher at Bogota-based think tank Instituto de Ciencia Política (ICP).

“It’s an attractive city not only to Colombians but to other Latin American travelers, who come seeking improved job opportunities, better quality of life and education, knowing that Bogota’s universities are the best in Colombia and among the best in Latin America.”

Transport is a major headache nationally. Unlike most other Latin American nations, Colombia’s economy is not concentrated. More than ten cities have populations in excess of 500,000 inhabitants. Medellin is known for its textile, pharmaceutical (ironic jokes probably unwelcome) and service industries. Barranquilla is another industrial hub – and chief Caribbean port. Cartagena de Indias, a sultry colonial jewel on the same coast, is the tourism hotspot. The three cities of Armenia, Pereira and Manizales constitute the “Coffee Triangle.”

While the even distribution of population and economic power is largely a positive, connecting up the cities of South America’s fourth-largest nation remains a challenge. Bogota lies atop an 8,600-foot plateau known as the sabana (savannah), bordered by the eastern Andean cordillera (chain of mountain ranges). Roads are in a terrible state of disrepair. Business people and tourists fly, even for relatively short distances. Six years ago, President Santos inaugurated the $70 billion Vias 4G infrastructure program, Latin America’s largest road-building initiative. It involves 47 projects spanning 5,000 miles of roads and 2,200 miles of four-lane highways as well as expansion of ports and railways, all to be completed by the end of the decade.

Invisible Exports

Tourism is, arguably, less an indicator of economic health than of good PR. But Colombia has some desirable unique selling propositions. It’s within easy reach of all the countries of the Americas: five hours from Atlanta, and 6.5 hours from Buenos Aires.

It’s the only South American nation with Pacific and Caribbean coasts. It has several well-preserved colonial cities, the three Andean ranges, the Amazon River as well as Magdale. It’s also one of the world’s 17 “megadiverse” countries, according to Conservation International, and is a favorite for intrepid birdwatchers.

ProColombia – the government body that promotes invisible exports – claims that, between 2010 and 2017, visitor numbers increased by 13.5 percent, almost three times the global average. International flights have grown accordingly, with Colombian flag-carrier Avianca – Latin America’s second biggest airline by fleet size and revenue – leading the way. A recent tourism campaign assured visitors, “The only risk is you’ll want to stay.”

But it’s not all a bed of hand-picked exportable roses. US government observers claim Colombia’s coca cultivation had increased 11 percent in 2017, and potential cocaine output rose 19 percent. Meanwhile, Duque’s past links with right-wing paramilitaries has raised questions about the future of the current detente.

Then there is the Venezuela problem. According to the Red Cross, more than one million refugees have arrived since 2017. Santos declared solidarity with the needy, but put more troops at the border. If anything, Duque is likely to tighten immigration controls.

By any standards, these are massive challenges. But consider Colombia’s point of departure. In the late Eighties, if Bogota wasn’t the global media’s “most dangerous city on earth,” then Medellin was, or Cali.

Over the past decade I’ve been to Bogota five times, and once each to the infamous “cartel” cities. In the capital, I was seduced by Bogotanos’ sophistication, bicycle-only Sundays, the energy of its young workforce, and in Medellin its public art, eco-minded civic spaces and new cable-car network. In Cali, it was the high-test firewater and scintillating salsa dancing – which is everywhere, and always was, even when times were really tough.

You’ve got to admire Colombia, but to really know its people you also have to enjoy yourself. If you go there on business, set aside time for pleasure – because there’s heaps of it on offer.